Last post, we looked at Ontario’s population and in

particular its concentration in the GTA and what I termed the GTAPlus or "The

Polygon" – a geographic area essentially going from Oshawa to the end of the

Niagara peninsula and then to Kitchener-Waterloo and finally out to Barrie and

back to Oshawa with Toronto approximately in the center. Approximately two-thirds of Ontario’s

population and by extension its economy are clustered in this small area whose

perimeter is about 500 km and encompasses a total area of nearly 14,000 square

kilometers and a land area of about 11,000 square kilometers. On a map of Ontario, this area looks like a

postage stamp and represents only about 1.3 percent of its area. Yet, well over

nine million people out of Ontario’s 14 million people live here and it

accounts for approximately 600 billion in GDP – nearly 70 percent of Ontario’s

economy.

In many respects, this core area has always been the heart

of Ontario’s economy but less so in the past in terms of its population, urban,

and economic dominance. There was a time

when Ontario had somewhat more dispersed and balanced urban and economic

development but the economic development of the last century has increasingly

concentrated economic activity in The Polygon.

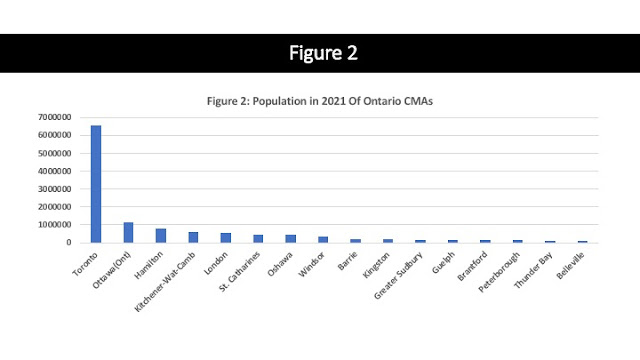

In order to provide some perspective on the evolution of Ontario’s

population over time, we start with Figure 1 which plots the population of

Ontario’s largest municipalities today ranked according to their 2021

population. These differ from CMA

populations – for example, while Hamilton is the third largest CMA in Ontario,

its municipal boundaries and population make it the fifth largest municipality

in Ontario after Toronto, Ottawa, Mississauga and Brampton. Population size today versus 1921obscures the size of these

cities 100 years ago so Figure 2 also plots the 1921 populations on their own.

Needless to say, the rankings have shifted somewhat over

time. London, Ontario was Ontario’s

third largest municipality in 1921 while Hamilton was fourth, Windsor fifth and

Thunder Bay (then the two Lakehead municipalities of Fort William and Port

Arthur) would have been Ontario’s sixth largest city. Ontario’s third and fourth largest cities

today – Mississauga and Brampton were essentially small towns in 1921. Indeed, much of the GTA outside of the City

of Toronto today in 1921 was at the bottom of the municipal population

rankings. Indeed, when one considers

these 30 largest municipalities (though Pickering and Ajax have been combined)

– 23 of them can be considered members of the Polygon. These municipalities alone account for nearly 9

million people in Ontario today, representing nearly two thirds of Ontario’s

population. However, in 1921, they

totaled about 700,000 out of Ontario 2.9 million for approximately 25 percent

of Ontario’s population.

Put another way, in 1921, nearly three quarters of Ontario’s

population lived outside the Polygon whereas today it is at best one-third. The increasing concentration of economic

activity and population in The Polygon – Ontario’s geographic top 1 percent so to speak – reflects the decline of resource sector (agriculture

included) and manufacturing industries that had dispersed population prior to

the mid 20th century. The relative

decline of cities such as Thunder Bay, Sudbury, London and Windsor – the North

and Southwest regions of the province – reflects this economic shift. The growth of the

Polygon cities reflects the rise of services and knowledge industries and the

increasing importance of having large urban agglomerations with economies of

scale and scope for associated industries and robust international connections to

world cities as the source of growth.

Is this a problem?

Well it depends on your perspective I suppose. The Polygon is a dynamic and growing

population and economic cluster in Ontario and is essentially Ontario’s gateway

to the international economy. While

small and compact, it has a very diverse population given it is the end point

for most of the international immigration into Ontario. By world standards, having 9 million plus people

clustered on 11,000 square kilometers – over 800 persons per square kilometer

– is not exactly at the top of the list. The Polygon is still quite roomy by world

standards. For example, the Hong Kong

SAR with an area of just over 1,000 square kilometers has about 7,000 people

per square kilometer. Nevertheless, for

the Polygon region to proposer, it will need continuing investment in

infrastructure not least of which will be housing. It will also need investment in quality of

life infrastructure such as green space and recreational facilities, not to

mention transit. Still, these challenges

represent opportunities for creative solutions and innovation. The most

important challenge is the institutional framework given the patchwork of

municipalities and jurisdictions in this area. Infrastructure development based on existing municipal boundaries is a sense fails to take into account the true scope of the Polygon as a growing and integrated region.

Some of those creative solutions will also need to address what

happens to those living outside The Polygon.

Here the challenges are more diverse.

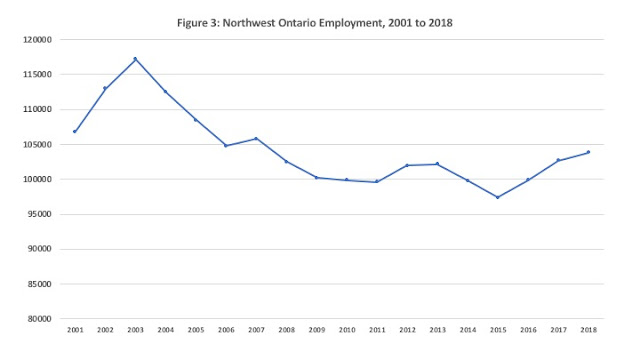

In the end, Ontario really consists of three regions - The Polygon, The Ottawa Nexus (Ottawa and the Kingston-Pembroke area) and then everyone else. Figure 3 outlines what this looks like in terms of distribution with the Polygon at closer to 10 million people here because Muskoka-Kawarthas are lumped into it for population purposes. The Ottawa region is the next largest outside of the Polygon but with

its role as the federal capital and its own relatively compact outlying region, it will easily

find its own solutions to its growth and development issues. More problematic will be those parts of

Ontario outside of the Polygon and Ottawa Nexus, the Southwest from London to Windsor

and upwards into the Bruce Peninsula and of course “The North” which with 90

percent of Ontario’s land area only has about 6 percent of the population. The interests of a high growth densely

populated region like the Polygon will differ from these slower growth and

lower population density parts of Ontario.

Needless to say, there will not be a one size fits all

solution to economic growth and development in these regions but their success

will ultimately all hinge on their ability to tap into opportunities offered by

the Polygon and how to market the goods and service of their regions there and

beyond. There is strength in numbers and

it is time for cities like Windsor and London in the Southwest, Thunder Bay and

Sudbury, in the North and Peterborough and Kingston in the East to forge better

relationships within their regions and with each other to promote their common

interests outside. These cities may have

greater success by magnifying their lobbying power and political influence

within Ontario by presenting a more

united front when it comes to economic development issues. Easier said than done? Yes, but when it comes to the economic

future, there is no say, only do.