Ontario’s economy has

increasingly become a tale of two regions – the GTA and everyone else. It is worth doing a quick review and update

of regional employment numbers (data from Statistics Canada) that provide some

additional insight on the past and the most recent distribution of regional

employment. In 2001, employment in

Ontario was 5.921 million jobs and over the period 2001 to 2018 it rose by 22

percent to reach 7.242 million jobs.

Figure 1 plots the growth rate of Ontario employment as well as for the

five major regions from 2001 to 2018 as well as for the sub-periods of 2001 to

2010 and 2010 to 2018.

In terms of overall

growth rates, employment expanded the most in the GTA, which saw an increase

between 2001 and 2018 of nearly 32 percent.

Indeed, the GTA’s share of Ontario employment during this period went

from 45 percent to 48 percent. The next

largest increase was for the area immediately adjacent to the GTA – central Ontario

- comprising of Muskoka and the Kawarthas, Kitchener-Waterloo-Barrie and

Hamilton Niagara. It saw growth of

nearly 23 percent in employment and its share of Ontario’s employment remained

constant at about 23 percent of the total between 2001 and 2018.

The next highest

growth rates were for Eastern Ontario and the Southwest respectively at 17 and

5 percent each. However, this employment

growth was not enough for both of these regions to hold their own in terms of

employment shares. While Eastern Ontario

maintained its 13 percent share of total employment between 2001 and 2018, the

Southwest saw a decline from 13 to 11 percent.

And then there is the

north which saw employment drop by 1 percent between 2001 and 2018 from 358,000

to 354,000 and its employment share of the provincial total drop from 6 percent

to 5 percent. Of course, this trend is nothing

new, but such an update is another reminder that despite a plethora of studies

and government pronouncements over time - including the Northern Ontario Growth

plan - there has not been a reversal of

northern Ontario’s economic fortunes.

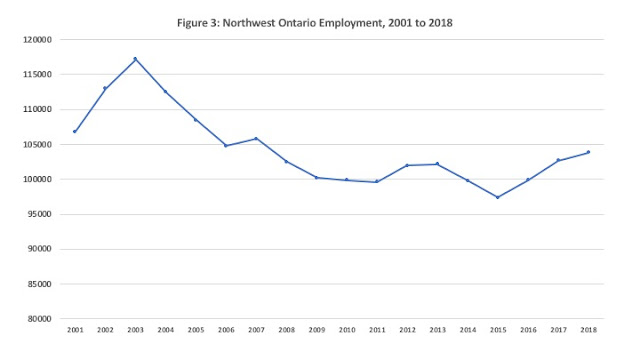

Figures 2 and 3 break employment over time in the Northeast and the Northwest. The Northeast reached its peak employment circa

2008 and has since generally trended down.

The Northwest peaked in 2003 and has trended down since though there has

been a slight rebound since 2015.

And there you have it - again.