Last week, I gave an economic overview of the challenges and opportunities facing northern Ontario’s economy at the Regional Meetings of the Economic Developers Council of Ontario in Thunder Bay. I covered a lot of ground, and it is worth presenting some of the highlights for the regional economy in terms of current indicators. This post, a quick overview of some of the key demographic trends that have been emerging in northern Ontario over the last while.

Figure 1 provides Census results from 2006 to 2021 and they show that despite the perceptions, northern Ontario’s population is starting to grow once again. While the period 2006 to 2016 saw a slight decline, the 2021 Census shows that population is up in both the Northeast and Northwest of the region. Between 2016 and 2021, northern Ontario’s total population grew from 780,140 to 789,519 – an increase of 1.2 percent (See figure 2) with the Northeast growing much faster that the Northwest. On the other hand, from 2011 to 2016, the Northwest grew substantially while the Northeast actually shrank.

Two other trends worth noting. First, while the conventional wisdom is that

the major urban centres in Ontario’s north are all major attractors of

population within the region, it turns out that between 2016 and 2021, Thunder

Bay, Sudbury and North Bay grew while Timmins and Sault Ste. Marie shrank

somewhat (See Figure 3). Second, the

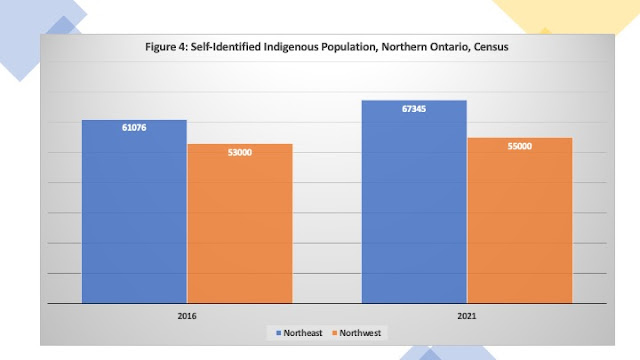

population that self-identified as Indigenous in the Census has been growing. According to the Census (See Figure 4) the Indigenous

population in the Northeast rose from about 61,000 to 67,000 (about a 10

percent increase while that in the Northwest grew from about 53,000 to 55,000 –

about a four percent increase. If one

adds up the two regions, in 2021 about 122,345 people in that year identified as

Indigenous in the north or about 15 percent of northern Ontario’s population. About 24 percent of the Northwest’s

population self-identified as Indigenous while 12 percent of those in the

Northeast did so. However, it should be noted that these figures may be an under count of the Indigenous population.

The trends are positive in that the region’s population is growing but the point to consider is that it is growing slower than Ontario as a whole. While Ontario’s population was up nearly 5 percent from 2016, the North is only up about 1 percent. This means northern Ontario’s share of Ontario’s population (which peaked in the early 1950s at nearly 12 percent) will continue to decline, all other things given. While 2021 saw the region’s share at 5.6 percent, according to Ontario government population projections, that share could decline to 4 percent by 2046. It is relative rather than absolute decline in population that is the real concern given that a declining share is also associated with declining long-term representation and influence within the province and the country.