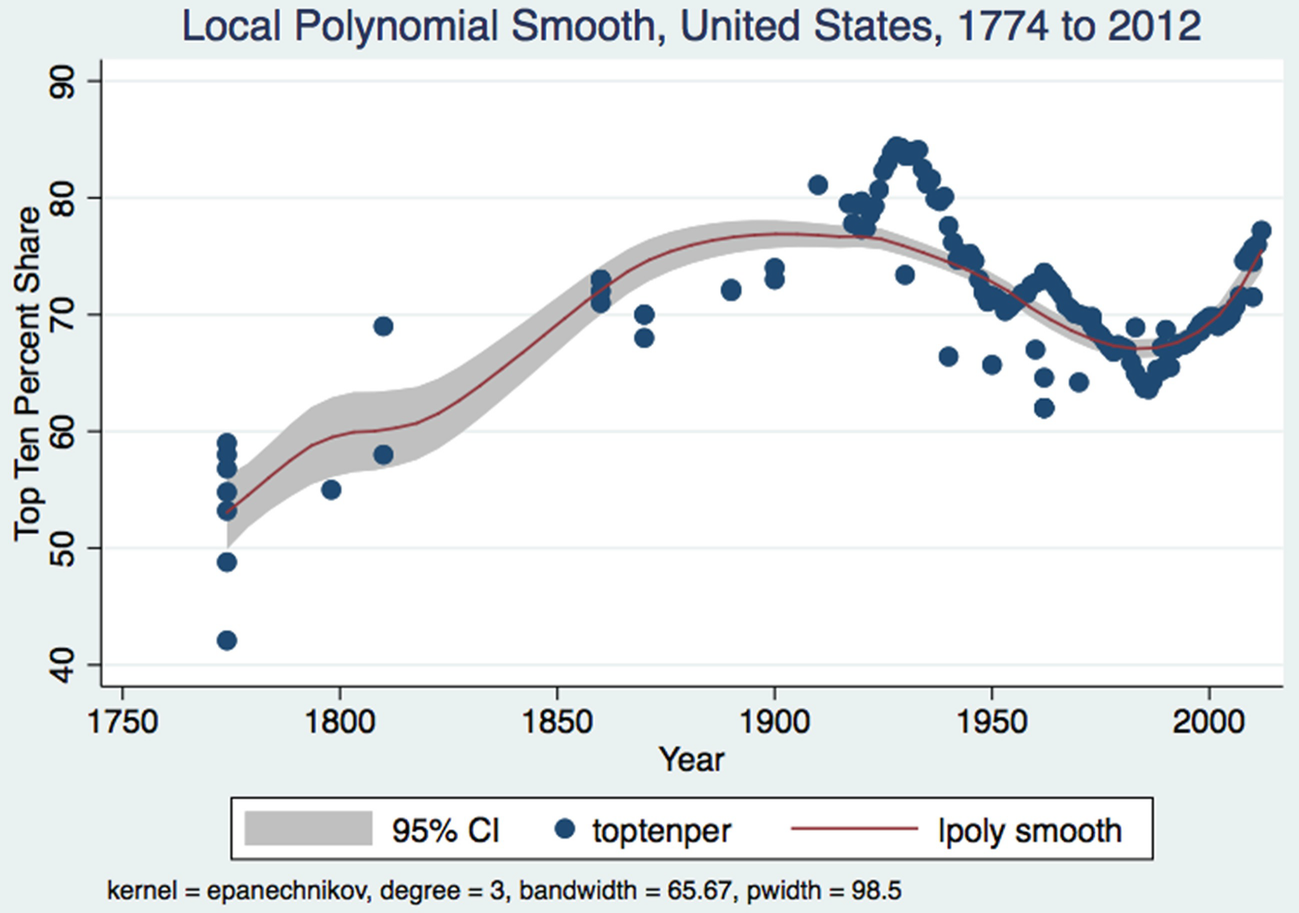

"Before 1750, wealth inequality was higher in the United Kingdom than the United States, but American inequality grew rapidly to match the United Kingdom by mid-nineteenth century. The preindustrial period was marked by lower wealth inequality in both the United States and the United Kingdom. The subsequent era of industrialization is marked in all three Anglosphere countries by rising wealth inequality. Wealth inequality declined in the twentieth century with redistribution away from the top one and ten percent. The decline in wealth inequality halted in the 1970s but with a rebound in American wealth inequality.

For the United Kingdom, the top 1 percent wealth share rose from an average of 25 percent in the pre-1850 period to 64 percent for the 1850 to 1900 period. More remarkably, the average share of wealth held by the top ten percent of the wealth distribution in the second half of the nineteenth century was just over 90 percent in the United Kingdom, approximately 72 percent in the United States and about 56 percent in Canada. By the early 21st century, Canada and the United Kingdom have their top ten percent with approximately 50 percent of wealth and the United States over 70 percent. Meanwhile the top one percent own just under 20 percent in Canada and the United Kingdom while in the United States the share is closer to 35 percent.

The twentieth century mitigation of wealth inequality correlates with several factors: rates of economic growth closer to the rate of return on capital, increased unionization rates, rising public spending on health and education, larger public sectors, increased home ownership rates, the onset of substantial estate taxation, more progressive income tax systems and in the case of the United Kingdom a housing policy that resulted in the disposition and dispersion of much public housing into private hands. A reduction in the strength of unions as measured by unionization rates as well as the end of estate taxation and less progressive income tax systems is associated with more economic inequality since the 1970s especially combined with lower economic growth rates relative to the return to capital."

You can also get quite a few bits of the book on Google Books if you want a free preview. The book surveys the evolution of wealth inequality as measured by the Gini Coefficient and the wealth shares of the top 1% and top 10% for Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom. A quick sample of one of the figures below on the wealth share of the top 1 percent in the United States from 1774 to 2012.

Anyway, it has been great working with Palgrave MacMillan and its staff in putting this project together and seeing it through. Am glad to see the book out.