Ontario is coming up to Budget Day next week on March 26th and it will be interesting to see what the provincial government does on a number of issues because quite frankly the provincial government is in a bit of a pickle when it comes to economic and fiscal policy. Over the last decade, Ontario has been hit by a productivity decline that has translated into slower economic growth. Since the pandemic, this has been combined with a bout of inflation and a surge in population growth. When you start looking at Ontario fiscal and economic indicators in real per capita terms, there are going forward disturbing implications for our standard of living.

If one compares the 2023-24 fiscal year forecast from the Fall Economic Update with the 2018-19 fiscal year, total provincial government revenues and expenditures are up approximately 30 percent respectively. Health expenditure is up 33 percent. The size of the provincial economy is up 22 percent. On the surface, this is seemingly good news in the wake of the pandemic. The problem is that over the same period, population in Ontario has grown by an estimated 12 percent while prices have risen nearly 19 percent. Put another way, the combination of population and inflation at nearly 30 percent has outstripped nominal GDP growth while essentially matching the growth of government revenues and expenditures and in particular health spending.

The best way to visually illustrate these effects is to create an index. Figure 1 uses data from Statistics Canada, the Fiscal Reference Tables and the 2023 Ontario Fall Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review to create real per person indices of economic and fiscal performance setting 2013/14 as 100. Figure 1 plots real per capita (deflated using the CPI-All Items Index) Ontario provincial government Own Source Revenue, Federal Transfers, Total Revenue, Program Expenditure, Debt Service Costs and Total Expenditures. Note that 2023-24 is an estimate.

In real per capita terms, debt service costs have been a bright spot in that despite the continuing rise in both the provincial net debt and interest rates, inflation and population growth have served to reduce the real per capita burden of servicing Ontario’s debt. Indeed, the drop-in debt service has probably been able to free up resources for program spending. On the other hand, compared to 2018/19, real per capita revenues and expenditures are now below where they were. In other words, provincial government revenue and spending have not kept up with inflation and more importantly population growth.

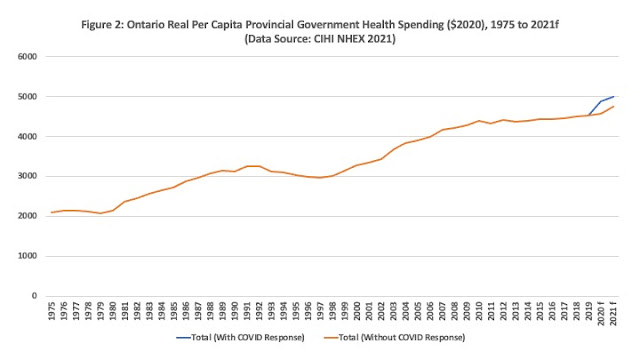

Figure 2 illustrates the decline in the Ontario way of life a bit more succinctly. Does the health care system feel strained? Real per capita provincial government health care spending after the surge of the pandemic is back to where it was in 2018/19. Indeed, it has not changed much since 2013/14. During that time, one imagines that labor costs for health care have gone up pretty dramatically which means there are indeed fewer doctors and nurses available to service a growing population. And to top it all off, real per capita output in Ontario has not kept pace with either inflation or population growth. While real per capita GDP in Ontario grew somewhat from 2013/14 to the pandemic, it has since declined.

Looking at Figure 2, if the average Ontario had to ask themselves am I better off than a decade ago when it comes to my real per capita income and health spending, the answer is one that should concern the provincial government.