A recently released

report jointly released by the Brookings Institute and the Martin Prosperity Institute

lays out Canada’s path to future prosperity via advanced industries and the

challenges Canada faces in this economic sector. The report is titled Canada’s

Advanced Industries: A Path to Prosperity and is authored by Mark Muro, Joseph

Parilla, Gregory M. Spencer, Deiter F. Kogler and David Rigby. These industries

are not just in manufacturing but span a number of diverse industries with the

commonality being the application of advanced technology and innovation. Brookings defines advanced industries as: “industries as diverse as auto and aerospace

production, oil and gas extraction, and information technology—are the

high-value innovation and technology application industries that inordinately

drive regional and national prosperity. Such industries matter because they

generate disproportionate shares of any nation’s output, exports, and research

and development.”

The report argues that

Canada’s advanced industries are not realizing their full potential and that

these industries need to be targeted to build a dynamic advanced economy for

future growth. About 11 percent of

Canada’s employment – about 1.9 million jobs – is currently employed in these higher

wage advanced industries and they generate 17 percent of GDP, 61 percent of

exports and 78 percent of research and development. Services account for about half of the

Canadian advanced industry worker base followed by manufacturing at about 36

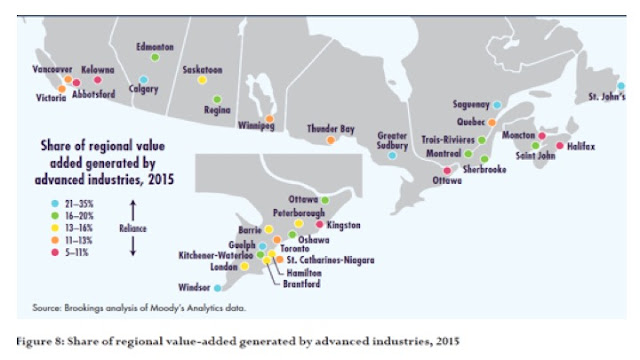

percent. What is more interesting is the

variation in scale, intensity and diversity of this sector across provinces and

Canadian CMAs.

Ontario, Quebec,

Alberta and British Columbia together account for 91 percent of advanced

industry employment which is just a bit more than their total employment share

which is about 87 percent. Not

surprisingly, the CMAs with the most advanced industry jobs are Toronto,

Montreal, Calgary and Vancouver. However,

productivity growth in this sector has been lagging relative to the United

states. What is particularly disconcerting from the point of view of northern

Ontario economic development however is the fact that every Canadian CMA added

advanced industry employment between 1996 and 2015 – the exceptions being St.

Catharine’s-Niagara, Greater Sudbury and Thunder Bay. Thunder Bay also ranks low when it comes to the regional value added generated by advanced industries (See figure taken from page 22 of report) whereas Sudbury does better because of the intensity of its mining sector. Moreover, Greater Sudbury and Thunder Bay are

also at the bottom of the CMA rankings when the number of advanced industry specializations

is compared in terms of local concentrations of activity.

Boosting advanced

manufacturing in Canada according to this report requires a strategy of “four C’s”

– capital, competition, connectivity and complexity. Capital is of course the most fundamental –

that is, investment in machinery and equipment but also knowledge capital such

as information and technology systems.

The weakness in business investment has been a long-known factor in

Canada. As for competitiveness, Canadian

industries have traditionally had less exposure to intense competition and this

may be limiting the capacity of its advanced industries to innovate. Fixing this requires greater market

competition and indeed deregulation and easing foreign ownership

restrictions. Connectivity involves

Canadian firms participating more in global value and production chains and

networks. Finally, complexity requires

firms to master the technological complexity and specialization of the modern

economy and this is often measured by patent activity which in Canadian CMAs is generally below American ones. Policies for building connectivity and

complexity in the end also involve the unleashing of greater competitive forces

within the Canadian economy in order to achieve the market size or scale within

which advanced industrial output can grow.

Thus, a major obstacle

for Canada when it comes to growing its advanced industrial sector is its

highly regional nature which in the end results in barriers to internal trade,

less competition and small market sizes that militate against the scale needed

to grow output. In the case of northern

Ontario, even with the growth in local entrepreneurship which has been quite

noticeable in its larger cities such as Thunder Bay and Sudbury, it remains

that without growth in market size, new innovative ideas will be like so much

seed fallen in rock if the companies cannot grow their output. In the end, any regional economic policy must

focus on increasing the scale of output by boosting market size either via

exports or via immigration and local population growth.