Thunder Bay City Council this week did

not support Mayor Ken Boshcoff’s desire to acquire “strong mayor powers” in

a quest to meet provincial targets for housing and reap the benefits of

associated funding support. In some respects,

this is not a surprise, not so much because members of council are so concerned

about local democracy but because it does represent an erosion of their power

given that strong powers on offer allow mayors to pass bylaws with the support

of just one third of council, as well as veto bylaws passed by council on

matters involving provincial priorities. In addition, the mayor will be able to

propose the city budget, reorganize city departments and hire or fire the city

manager and even some department heads. If anything, this represents a major potential increase in workload for the Office of the Mayor and one suspects there will eventually be some hiring to provide the necessary support.

Thunder Bay City Council because of its unique structure of at-large and ward councillors has always had councillors whose electoral mandate pretty much matched that of the mayor given they were elected by city-wide voters. What the new changes mean in Thunder Bay and indeed in municipalities across the province is that the power structure has been unilaterally changed by the province in an effort to get the provincial housing agenda kick-started. Indeed, going down the road, what some future mayor might do with such powers is a real concern. Nevertheless, it would appear that the mayor is going to ask for those powers with or without council support because the mayor wants to commit Thunder Bay to a target set by the province of 2,200 new homes by 2031.

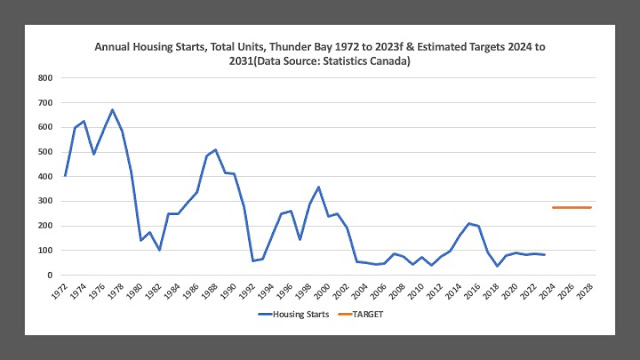

This target is an interesting one because it means that over the next eight years (2024 to 2031), Thunder Bay needs to build an average of 275 new housing units annually. The accompanying figure plots the annual number of housing starts from 1972 to 2023 and also plots the annual target set at an average of 275 units per year. The 2023 estimate is incomplete given that the numbers from Statistics Canada only go to August and the monthly average based on January to August is used to fill in the rest of the year. Even that total seems an underestimate given the couple of large apartment projects that have emerged that might double the total for 2023.

Needless to say, the target is an ambitious one given that since 2000, the annual average works out to about 105 units per year. In other words, going forward, it will be expected that Thunder Bay has to achieve just over 2.5 times the number of starts than it has managed on average over the last two decades.

Can a strong mayor somehow wield the influence and power to more than double the number of housing starts in Thunder Bay? Given the shortage of building trade workers as well as the fact that for the houses to be built, there has to be a demand for the housing and interest rates have spiked at the moment, it will be a challenge. Then there is the ability of developers to earn a profit on the new builds whether single detached houses, apartments, or condos, even with whatever financial support the province has in mind. Again, one suspects this target may be a tough one to reach. A lot depends on whether or not there really are a lot more people in Thunder Bay than official counts say there are and if those people are actually interested in permanent housing in Thunder Bay and more importantly have the ability to pay for it either as owners or renters.

One suspects that in the end, the real influence of strong mayor powers in Thunder Bay will not be so much on the future housing stock but on things like the city budget and even senior staffing. The mayor’s position is about to get more important and as the adage goes, with great power comes great responsibility.