Given the ongoing municipal

election campaigns in Ontario, I have been focusing a fair amount of my

blogging activity on municipal

public finance issues. In a

recent post, I looked at the Net Municipal Levy Per Capita (NMLPC ) for the

five major northern Ontario cities for the years 2007 and 2017. In 2007, the

NMLPC was highest in Thunder Bay at $1,216 and lowest in Sudbury at

$1,041. By 2017, spending was highest in

Timmins at $1,651 (with Thunder Bay second at $1,641) and lowest in Sault Ste.

Marie at $1,434. If one compares the

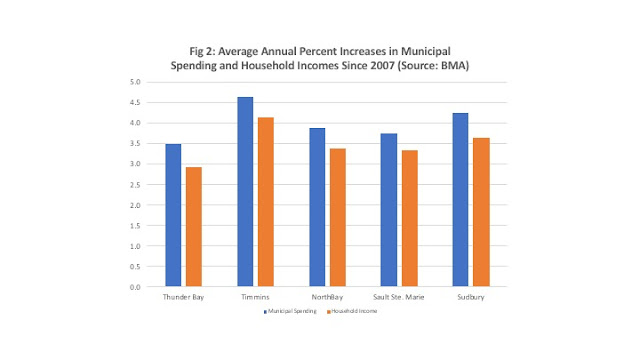

growth rates in the per capita levy, they were actually highest in Timmins at an

average of 4.6 percent annually and lowest in Thunder Bay at 3.5 percent

annually. I also compared the growth of

the NMLPC to household income growth and showed that per capita municipal

spending has been rising faster than average household income raising the question of sustainability.

In this post, I want

to drill down a bit in the total expenditure numbers and compare spending for

these five major northern Ontario cities in a number of key municipal expenditure

categories. The data is from the 2017 BMA

Consulting Municipal Report and was available for key expenditure categories in

terms of the levy for the category per $100,000 of municipal tax assessment. In order to standardize comparison, I have

reproduced the net levy graph (Fig 1) but per $100,000 of assessment rather

than per capita as in the last post. To

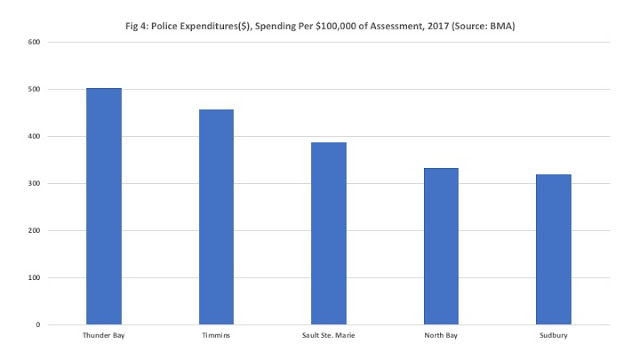

this I have added graphs comparing general government (Fig 2), fire (Fig 3),

police (Fig 4), paved roadway spending (Fig 5) and winter control (Fig 6). Keep in mind that this is data for only one

year and there are differences in population size and geographic spread across

these five cities as well as any unique local circumstances that may affect

spending.

Nevertheless, the

results are illuminating in that there is no one size fits all pattern of

spending across these five communities when it comes to these key municipal

expenditure categories. The net levy per $100,000 of assessment ranges from a high of $2,136 in Timmins to a low of $1,482 in Sudbury. Thunder Bay

spends the most on general government (i.e. administration) at $257 per

$100,000 of assessment and Timmins the least at $65. North Bay spends the most on fire services at

$283 per $100,000 of assessment and Sudbury the least at $160. In terms of policing, Thunder Bay spends the

most at $503 per $100,000 of assessment and Sudbury the least at $320.

When it comes to paved

roadway expenditure, Sudbury spends the most at $258 per $100,000 of assessment

and Sault Ste Marie the least at $101.

Finally, all five of these cities experience harsh winters and the need

to plow roads and when you look at winter control spending, Timmins spends the

most at $237 per $100,00 of assessment and Thunder Bay the least at $48 per

$100,000 of assessment. This last

category however is the most likely to be the subject of large fluctuations

from year to year given local weather conditions. My guess is the winter of 2017 was pretty bad

in Timmins.

Overall, there are

large differences in spending across these categories across these five

cities. The spending in these categories

on average across these five cities in 2017 accounted for about two-thirds of

the net levy – a significant proportion.

It would be

interesting to know what the incidence of fires is in North Bay and

Thunder Bay given the size of the expenditure in these communities

compared to the others. Given high homicide rates in Thunder Bay, it is understandable perhaps why it spends the most of police of these five cities. Yet, given that the average proportion spent

on governance in these five cities is about 8 percent of the net levy, one

wonders why Thunder Bay spends 14 percent and the Sault is at 11 percent

compared to say 3 percent in Timmins or 9 percent in Sudbury.

Ratepayers in each community should be asking themselves how their community compares to the others and what may be driving the differences. Is the best value for money being provided?

Ratepayers in each community should be asking themselves how their community compares to the others and what may be driving the differences. Is the best value for money being provided?