I have been working on an article surveying the economic history of northern Ontario and thought a summary overview draft of where I am going with it would be a worthwhile post. The entire article is going to be much more detailed but this excerpt below provides a pretty good overview of the direction it is going. Enjoy.

A Very Brief Survey of Northern Ontario Economic History

Livio Di Matteo

Northern Ontario’s

economy began in the 19th century as a booming resource frontier as

a result of favourable international market demand for natural resource commodities which were supplemented by government policy initiatives in transportation and protectionism.

Export-led growth approaches to development suggest that such a growth process

can ultimately expand population and market size leading to self-sustaining

economic growth, but Northern Ontario never made that transition and in the

latter part of the twentieth century and early twenty first century can be

viewed as having undergone arrested development.

Northern Ontario is a vast region of over

800,000 square kilometers covering about 90 percent of Ontario’s land mass. While long the home of a substantial and well

organized indigenous and First Nation population[1],

industrial economic development of northern Ontario under European settlement began in the 19th century as a

booming natural resource frontier driven by rising international market demand

for natural resource commodities – mainly forest and mineral products –

combined with government policy initiatives in transportation infrastructure and economic

protectionism via what was known as the Manufacturing Condition.

In defining the region, it is important to

note that is geographically, geologically and biologically a distinct region

traditionally defined as the area of Ontario north of the French River – Lake

Nipissing – Mattawa River system. It is

essentially Precambrian shield made up of some of the oldest rocks in North

America and as a result of glaciation scraping its soil consists of shallow

soils with some alluvial soil deposits in areas such as the Clay Belt regions

and a mainly boreal forest ecology consisting largely of coniferous forest.[2]

In defining the region there is the

question of borders as some include the Districts of Muskoka and Parry Sound in

northern Ontario – as indeed they are for the purposes of federal and

provincial regional development policies – while other might consider them not

as the north but the ‘near’ north.[3] There is also the question of thinking about

the north as a region given that it is a very diverse area that in many

respects is not one north but ‘many’ norths.[4]

Geographically, there is the Northwest

consisting of the Districts of Thunder Bay, Rainy River and Kenora while the

other two-thirds of the region is the Northeast consisting of Cochrane,

Timiskaming, Algoma, Sudbury, Nipissing and Manitoulin. There is also the vast sparely populated area

north of 50 which in some respects does not fit into either the northeast or

northwest except by government fiat. And

of course, there is a rural remote north of small towns and Indigenous reserves

as well as an urban north consisting of the five major cities – Thunder Bay, Sault

Ste. Marie, Timmins, Sudbury and North Bay.

And the Northeast is also marked by a strong francophone population

component while the region as a whole has a large Indigenous population.

The themes of Northern Ontario’s economic

development are three-fold: natural resources, transportation and government.[5] Northern Ontario’s economic development can

easily be discussed within the framework of economic staples – products with a

high natural resource content – given the importance of fur, lumber, pulp and

paper and mineral products to the north’s economic history. As for

transportation, this is a key theme given the importance of the Canadian

Pacific (CPR) and Temiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway (TN & O) in

providing access to northern Ontario resources in the 19th and early

20th centuries as well as providing the means for them to exit the

region to world markets. Finally,

government is important given the federal role in providing transportation

infrastructure that accessed and served the North such as the CPR, the

Trans-Canada Highway and the St. Lawrence Seaway as well as the Ontario

government given its parallel regional development program in the 19th

century consisting of the building of the TN & O as well as the

protectionist Manufacturing condition and its own agricultural land settlement

policy.

Given the importance of natural resources

to northern Ontario’s economy, the analytical framework best-suited to

outlining the causal relationships of the development process is the Staples

Approach or more generally, models of export led development. The Staples approach sees a region’s natural

resource base as the most important determinant of both the pace as well as the

patterns of economic growth with the classic exposition provided by Harold

Adams Innis who viewed economic development as springing from the interplay

between an industrial heartland and a resource reducing hinterland.[6] In the case of northern Ontario, it can be

viewed as a resource hinterland not only to the industrial south but also the

rest of the world economy given the international market for its mineral and

forest products. More modern versions of

the Staples Approach see economic development as the process of diversification

around an export base with the degree of diversification a function of what are

termed economic linkages. These linkages

involve producing inputs for the resource export sector or investing in

industries that use the output of the export sector as an input as well as the

final demand for domestically produced consumer products.[7]

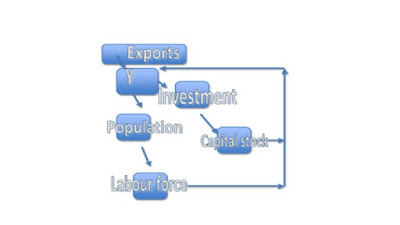

Figure 1 outlines the export led/Staples

growth process with an increase in exports generating an increase in the

regional economy’s output/income (Y).

The presence of rising income and economic opportunity in the resource

sector leads to population increase both via natural increase but also

migration into the region. This leads to

an increase in the labour force which feeds back into the generation of

income. As well, the increase in income

leads to an increase in regional saving which fuels investment as well as

external investment flowing into the region to provide the capital stock needed

to expand production of the resource export.

This process continues in a circular fashion until both the income and

population become large enough to provide a market for regionally produced goods

and services on top of the export sector and it is this expansion of regional

manufacturing production as well as services to meet local needs and substitute

for imports that becomes the process of diversification. A failure to grow and develop beyond the

initial export industries that powered development can be seen as incomplete or

arrested development.[8]

Figure

1: A Model of Export-Led Growth

The economic history of northern Ontario can be divided into a number of stages. They are: 1) Pre-European Settlement to 1867, 2) Boom, Colonialism and European Settlement, 1867 to 1913, 3) Consolidation, Depression and War, 1914 to 1945, 5) Post-War boom, 1946 to 1969 and 6) Arrested Development: Economic Dependency and Decline, 1970 to the Present.

The economic development of northern

Ontario followed a process of export-led growth fueled in particular by the

export of mineral and forest products.

International demand and private sector exploitation of the region’s

resource abundance starting in the 19th century was also accompanied

by investment in transportation networks to bring resources out to market and

government policies and initiatives designed to help facilitate development as

well as take advantage of the public sector revenue potential of these

resources. Within this framework then,

the three major engines of northern Ontario economic development are natural

resources, transportation and government.

During each of northern Ontario’s

development periods outlined here, economic growth was most robust during eras

where all three engines came together to provide the impetus for economic

growth and employment creation. The most

robust economic growth and development occurred during the eras from 1867 to

1913 and 1946 to 1969. Both of these

eras coincided with good global economic conditions which fostered a demand for

resource products and led to private capital investment in production

facilities and transportation networks.

Both of these eras also saw a large spending and policy role for

government which facilitated development. The first era also saw northern Ontario as a major source of provincial government revenue.

Growth was poorer in the 1914 to 1945 as a

result of erratic global markets, private sector weakness and the retreat of

government involvement in northern development after the onset of the Great Depression

and yet this was still an era of substantial population growth. Economic growth since 1970 in the region has

essentially stagnated along with population growth as a result of long-term

technological change which reduced the labour intensity of natural resource

extraction in the region. While

government did undertake more interventionist activity in an effort to arrest

northern decline, it has failed to reverse the slow growth nature of the region

given the absence of supporting private sector investment.

[1] By the 17th

century, the mainly Algonkian culture Anishnawbe and Cree indigenous population

had developed a seasonal woodland economy and lifestyle centered on hunting and

trading. See Bray and Epp (1984: 8).

[2] See Robinson (2016: 8-9) for a fuller description of the

region. The glaciers of the various ice

ages periodically scraped topsoil off in northern Ontario and deposited it

further south ironically enough making nature responsible for the first set of

“resource transfers” from Ontario’s north to the south. According to Louis

Gentilcore (1972: 7-8): “The acid nature of the podzols, the slower breakdown

of the vegetable matter, and the prevalence of peaty soils create problems in

the utilization of the soils of northern Ontario for commercial agriculture.”

[8] Part of this process

of arrested development could also be referred to as a Staples Trap whereby an

economy is not able to move beyond its initial export sector activities. For a discussion of the Staples Trap see

Watkins (1963).

References

Bray, M. and E. Epp, eds. (1984) A Vast and

Magnificent Land: An Illustrated History of Northern Ontario. Ontario Ministry

of Northern Affairs.

Di Matteo, L. (1991) “The Economic

Development of the Lakehead During the Wheat Boom Era: 1900-1914,” Ontario

History, LXXXIII, 4, December, 297-316.

Di Matteo, L. (1999) “Fiscal Imbalance and

Economic Development in Canadian History: Evidence from the Economic History of

Ontario,” American Review of Canadian Studies, Summer, 287-327.

Innis, H.A. (1930/1984) The Fur Trade in

Canada, Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Miller, T. B. (1985) “Cabin Fever: The

Province of Ontario and its Norths.” In D.C.D.C. MacDonald, ed., The Government and Politics

of Ontario. 3rd ed. Scarborough:Nelson, Canada, 174-191.

Ontario (2011) Places to Grow: Growth Plan

for Northern Ontario. Toronto: Ministry

of Infrastructure and Ministry of Northern Development, Mines and Forestry.

Robinson, D. (2016) Revolution or

Devolution?: How Northern Ontario Should Be Governed. Northern Policy

Institute. Research Paper No. 9, April.

Watkins, M. (1963) “A Staple Theory of

Economic Growth,” Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, 29,

141-158.