With all the doom and gloom about the finances of Canadian universities these days, it is refreshing to know that some universities have been doing well in coping with all the fiscal challenges thrown at them over the last decade. Nowhere is this more the case than in Ontario where domestic tuition fees were cut 10 percent in 2018 by the province, and have remained frozen since, provincial government grants have generally been a declining source of revenue and the flow of international students curtailed by the federal government. While Ontario produced Laurentian, it has also produced Lakehead where the last decade has seen a better financial performance than one might have expected which is good news for Thunder Bay, northwestern Ontario and of course the students, staff and faculty at Lakehead.

The evidence is quite convincing. Figure 1 (and subsequent figures) takes data from the audited financial statements of Lakehead University from 2014 to 2025 and plots total revenues and expenditures. Between 2014 and 2025, Lakehead’s total revenues grew from $177.3 million to $246.0 million - 38.7 percent – while total expenditures grew from $167.0 million to $230.5 million – a 38 percent increase. While the pandemic period from 2020 to 2022 saw a dip in revenue growth, since 2022, revenues have managed to grow faster than spending. Indeed, over the period 2015 to 2025, the average annual growth rate of revenues was 3.3 percent compared to 3.0 percent for expenditures.

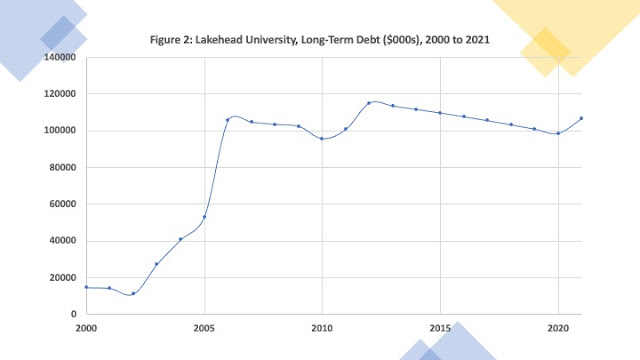

The result has been a decade where the budget has usually been balanced, sometimes with substantial surpluses, and the long-term debt been reduced. Figure 2 plots Lakehead University’s deficits (-)/surpluses (+) as well as the total long-term debt again from 2014 to 2025. Out of these 12 budget years, Lakehead ran a surplus 75 percent of the time with an accumulated surplus of $43.9 million while the long-term debt has decreased nearly 16 percent going from $111.5 million in 2014 to $94.0 million in 2025. The worse deficit year was 2022 with a deficit of $16.7 million in the wake of the pandemic but the three years since has seen growing surpluses with 2025 at $13.5 million.

Drilling down into some of the data, Figure 3 presents the data for Lakehead’s major revenue sources – provincial government grants and student fees. In 2025, these sources made up 82 percent of Lakehead’s revenue with the remainder a combination including investment income, research income, ancillary fees, and sales of goods and services. The narrative regarding provincial government grants should be nuanced by the fact that there are the general operating grants and then more specific restricted grants tied to conditions. In 2014, the value of the operating grant was $65.3 million, and it then proceeded to decline through to 2019 when it reached $62.9 million. Note that this decline preceded the arrival of the Ford government in 2018 showing that in the end universities in Ontario do not have any tried-and-true political party friends at the provincial level. Grants then rebounded in 2020 declining to a low of $61.6 million in 2022. Since 2022, the operating grant has been somewhat erratic rising to $66.7 million in 2023, falling to $61.0 million in 2024 and then climbing again to $69.5 million in 2025. Stable funding it is not. As for restricted grants, they climbed in fits and starts going from $15 million in 2014 to almost $17 million by 2021 and then rising more steeply to 30.5 million in 2025.

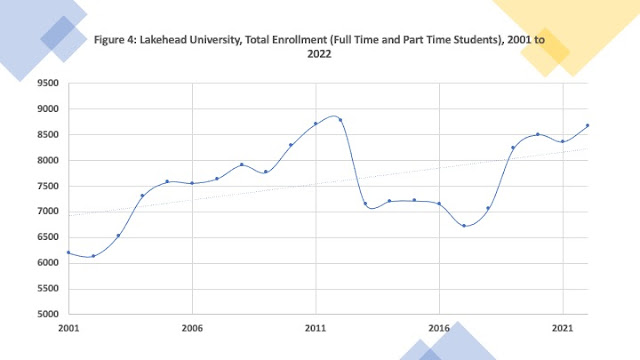

While total provincial grants to Lakehead grew 25 percent from 2014 to 2025, the real revenue story is in student fees which rose from $57.5 million to $102.4 million – an increase of 78 percent. This is even though overall enrolment has grown but not in leaps and bounds. The revenue increase is largely the result of a compositional shift as more higher tuition paying international students arrived at the university. Given that many of these students are primarily graduate level and in disciplines that are in demand, it appears the immigration restrictions have not hit Lakehead’s enrolment as hard as some other universities. This suggests a careful mix of programs tailored to demand.

So, to summarize, Figure 4 presents the average annual growth rates of these major indicators for the 2015 to 2025 period. Total revenue at Lakehead has grown at an average annual rate of 3.3 percent while expenditures have grown 3 percent. This in and of itself presents a picture of fiscal sustainability rooted on both the expenditure and revenue side. While general operating grants have only grown at an average annual rate of 0.7 percent, restricted grants (targeted to some purpose) have grown 8.7 percent annually and student fee revenue has grown 5.5 percent. And the icing on the cake is that long-term debt has been declining at -1.5 percent annually.

This is extremely good news and evidence that even in today’s challenging university environment, it is possible to succeed both financially and academically as a university offering programs in a fiscally sustainable manner. Lakehead has managed this operating as it does in a dispersed fashion with campuses in Thunder Bay, Orillia and Barrie making it a province wide university. This success may indeed serve as a model for future of Ontario’s universities. This success is also a testament to the strength of its board and administrative leadership as well as its students, staff and faculty. It is nice to have some good news for a change.