Thunder Bay has signaled that it wishes to increase urban

density by enacting a new

zoning bylaw in April

of 2022 designed to encourage urban density through a process of infill. One of the more controversial changes is that

the urban low rise neighborhood designation now permits buildings that can contain

one to four homes based on the size of the property. Most buildings in such neighborhoods can now

be permitted to contain two homes – mainly basement apartments or “mother-in-law”

suites but backyard homes will also be allowed.

In some respects, this legitimates a process that has already been

underway in many neighborhoods given the persistent housing shortage that seems

to be present even in Thunder Bay - a city whose official population has not

grown that much since 1971. And as part of the move to create new housing and

urban density, there is now a

move underway to consider reviewing surplus City of Thunder Bay land for

the purposes of selling it for infill housing. Of course, there is the usual

inconsistency in that while wanting to increase density in

existing residential neighborhoods, Thunder Bay is expanding standard suburban developments at the same time which often reduce urban density.

Ultimately, the policy of allowing more units on a standard-lot

or the renting of basement apartments is really an infill policy done on the

cheap by piling more people onto existing infrastructure and services and not worrying too much about any disruption or other social costs. In addition, more people living in current

suburban residential areas removed from shops and services simply perpetuates a

car intensive community. True density

housing should be built adjacent to or in the two main downtown cores with

secondary core density areas being areas like perhaps Westfort or the Bay-Algoma

area. True density housing is not a single

detached home or duplex that accommodates renters on an existing lot in River

Terrace or Vickers Park, it is two and three-bedroom apartments in 4 to 6 story

buildings and sometimes even higher, situated adjacent to core areas with a lot

of shops and services. In this regard,

even parts of intercity near shopping malls could be considered a location for

an apartment building or condo though the swampy nature of the area probably

militates against high rise construction. If the city has surplus land and buildings in these core

areas, that is what should be used to stimulate density.

And of course, just selling land and hoping that if you sell

it, they will build, is ultimately not enough. You probably need to streamline

the permit and approval process as well as rebate those costs with the amount

of the rebate tied to the speed with which the building is constructed and put

on the market. In addition, you probably need to lower the property tax rate on

such structures to make them more lucrative for developers to build density

buildings. This is a key point and a

neglected one. To start, take a look at

figures 1 and 2. Figure 1 plots population

density as a proxy for urban density in Ontario’s thirty largest municipalities

and Thunder Bay ranks fifth from the bottom.

Figure 2 takes those same municipalities and plots their multi-residential

total property tax rate from highest to lowest.

It turns out that Thunder

Bay has the third highest multi-residential rate – just after Chatham-Kent and Windsor. According to the 2022 BMA Municipal Report analysis, the

average multi-residential rate in Ontario communities was 2.04% but in Thunder

Bay it was 3.12%. Other examples include Brampton 1.56%, Hamilton, 2.73

percent, Burlington 1.45%, Sault Ste Marie 1.77%, Greater Sudbury 2.98%,

and Guelph, 1.99%. Elliot Lake is higher at

4.0%, Belleville at 3.24%, Port Colborne at 3.45%, and Timmins at 3.35%. My point is larger cities - of which Thunder

Bay is still considered one - tend to have lower rates but Thunder Bay taxes its

multi-residential more like a much smaller town. Why is Thunder Bay so spread out? True density is penalized by its property tax

structure.

Now it should be noted that a high multi-residential property tax

rate in and of itself is not evidence that it is discouraging density development.

In general, municipalities with weaker tax bases tend to have higher rates in

general to provide the same range of services often mandated by the provincial

government. In this respect, Thunder Bay

is in good company with other cities whose former lucrative industrial tax base

has seen decline – Windsor, Sudbury, Hamilton, and St. Catharines. Thunder Bay just has high rates in general and

it also has the third highest residential tax rates of these thirty

municipalities.

What is more relevant is not the multi-residential tax rate

per se but the difference between the multi-residential rate and the

single unit residential rate in a given municipality.

The greater the gap between the multi-residential rate and the

residential rate applied to a given value of assessed property, the greater the incentive to

build single residential housing units as opposed to multi-residential units. While Thunder Bay has some of the highest

residential and multi-residential total property tax rates in the province, it

also has one of the highest differences between the two. Relatively speaking, the larger the gap, one would expect a

greater tax disincentive to invest in large multi-unit residential properties,

all other things given. As a result, one

would also expect to see a relationship between the size of the gap and the

degree of urban population density with a larger gap correlated with lower

population density.

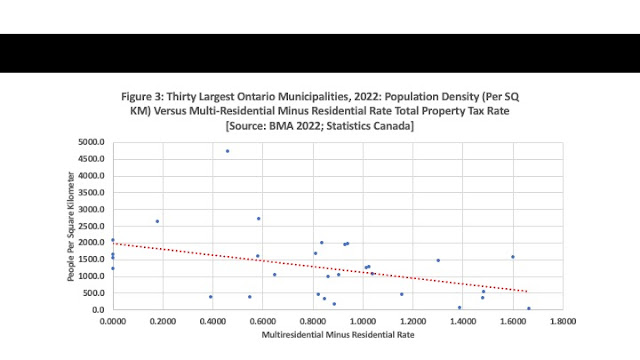

Figure 3 tries to do exactly that. It plots a scatter-plot for Ontario’s thirty largest

municipalities of municipal population density as a function of the difference between

the two rates. The larger the difference

-that is the higher the gap between multi-residential and residential property rates

– the lower the population density, all other things given. Of course, all other things are not given and

there may indeed be other variables influencing urban density not just in

Thunder Bay but other cities as well. After all, robust economic growth that pours

more people into a fixed geographic space is also a way to increase population and

urban density. However, parsing

everything out would require a fairly expensive study – this is after all, just

a blog – but that would mean paying a lot of money to consultants for answers

Thunder Bay City Council and Administration probably do not want to hear.

Namely, Thunder Bay’s municipal tax system and development policies discourage

density and encourage sprawl. Rule of

Thumb. If you want less of anything, tax it more heavily.