This post originally appeared on the Fraser Institute Blog, February 24th, 2024.

Ontario’s housing woes—a supply-side problem

Housing prices in Ontario, like in much of the rest of Canada, have soared because of several factors including supply constraints combined with rising demand fuelled by robust population growth. The most recent installment in this ongoing saga is the federal government’s move to cap international student visas to which Ontario has announced measures requiring universities and colleges to guarantee student housing—though how this is to be done is a good question.

These short term reactive regulatory actions at both the federal and provincial level will ultimately do little to solve the problem of scarce and expensive housing because they do not address the root of the problem—the supply side, particularly the high cost of building new homes, which results in meagre efforts to build new housing stock.

Aside from the recent labour shortages and run-up in construction costs in the pandemic’s wake, there are two additional facets to the supply and cost-side issues of housing in Canada in general and Ontario in particular.

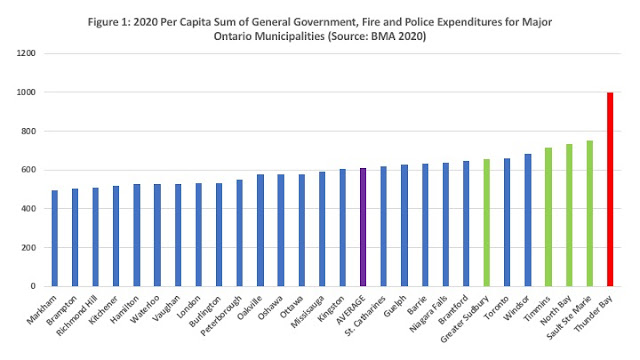

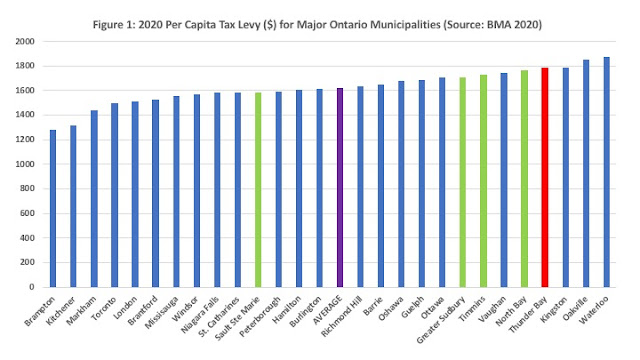

First, there’s the role of government in driving up the cost of new housing through regulatory actions at the provincial and municipal level. Housing in early 21st century Ontario has been treated not as an investment but as a source of cash for governments, which always seem to need more money. According to a CMHC report, government charges on new housing development via warranty fees, municipal fees, development and permit fees easily add 20 per cent to the cost of building a new home. Indeed, the regulatory charges for a new home in a place such as Markham can easily add up to $180,000 with some of the higher costs imposed on higher density row homes and high rise units relative to single-detached homes. This is not an inconsequential amount given housing prices in Markham average about $1.3 million.

Second, housing supply has not kept up with population growth. This is not a new story—the addition of new per-person housing stock in Ontario peaked in the 1970s. The chart below plots total housing starts for Ontario from 1955 to 2023. While there have been cyclic highs and lows, the overall trend has been upwards. Even so, the total number of starts peaked in 1973 at 110,536 starts. By way of contrast, 2023 saw 89,297 new home starts. In 1973, Ontario’s population was 8.1 million people whereas by 2023 it was estimated at 15.8 million.

When one calculates the number of new starts per person and constructs an index with 1955 equal to 100, it becomes clear that new housing starts per person have been on a long-term decline. Compared to 1955, we’re building 45 per cent fewer new homes per person. If you compare it to the per-person peak in the 1970s, Ontario in 2023 built nearly 60 per cent fewer new homes per person.

To add to the stock of affordable housing, the Ontario government has set the target of 1.5 million homes to be built by 2031. To this end, it created a Building Faster Fund that would provide up to $1.2 billion to municipalities that meet or exceed the government housing target set for that community and provide strong mayoral powers to municipalities to help cut through municipal red tape and speed up construction. The government has also set housing targets for municipalities to meet to receive the funding.

Keep in mind that to reach a target of 1.5 million new homes by 2031, Ontario would need to add 187,500 new homes a year until 2031. As the first chart illustrates, since 1955 there has not been a single year where Ontario has come close to that number. Indeed, if one compares housing starts as a per cent of the target set by the provincial government across municipalities based on data from its Housing Tracker (see chart below) it’s clear that as of late-January 2024, barely one-quarter of municipalities had met their 2023 housing target. Not the most auspicious start.

What’s Ontario to do? The province’s housing availability and affordability problem will likely get worse before it gets better. Along with boosting the supply of skilled trades people to help construct more homes, it must reduce the regulatory and zoning barriers that slow down the construction of multi-unit residential projects, reduce the governmental development charges particularly on “missing-middle” density builds that emphasize family-sized units, and provide further tax incentives geared to building high-rise multi-unit builds with family-sized units. Governments should also increase efforts to leverage surplus public lands at the federal, provincial and municipal levels to help construct affordable housing as the current approach has paid little attention to having a constant and ample supply of shovel-ready sites.

Only such a multi-pronged approach will have any hope of meeting the housing needs of Ontarians over time.