We are about three

weeks out from the municipal election and across northern Ontario, voters will

be looking for information on which to base their decisions. Inevitably, some of that decision making will

be based on comparisons of how municipal ratepayers feel they fare relative to other

similarly sized cities. Taxes are often

the basis of such comparisons, but municipal property taxes are a function of what

municipalities spend so another basis for comparison is expenditure.

Among the many

municipal statistics provided in the annual BMA Municipal Study is fairly

detailed comparisons of spending on municipal services. The aggregate number on which any comparison can

begin is what is known as the net municipal levy per capita (NMLPC). This is an estimate of what the spending need

for a municipality is to provide its services – as determined by the city administration and elected council – and ultimately is what feeds into required tax

revenues.

Now the BMA reports

are quite explicit in qualifying what a NMLPC measure can and cannot do and what its

limitations are. Spending per capita can

vary as a result of different service levels as well as type of service. There are also demographic and socio-economic

reasons why spending may vary across cities and per capita spending is simply

an aggregate and not an indicator of value for money. However, the BMA maintains that changes in

per capita spending reflects changes in total spending relative to population

and “Increasing per capita expenditures

may indicate that the cost of providing services is outstripping the community’s

ability to pay, especially if spending is increasing faster than the resident’s

collective personal income.”

So, the accompanying

figure 1 shows the NMLPC for the five major northern Ontario cities for the

years 2007 and 2017. In 2007, the NMLPC was highest in Thunder Bay at $1,216

and lowest in Sudbury at $1,041. By

2017, spending was highest in Timmins at $1,651 (with Thunder Bay second at

$1,641) and lowest in Sault Ste. Marie at $1,434. If one compares the growth rates in the per

levy, they were actually highest in Timmins at an average of 4.6 percent

annually and lowest in Thunder Bay at 3.5 percent annually.

However, in all of

these cities, per capita spending grew faster than population suggesting that

there was a deepening of per capita spending.

That could be the result of a desire to improve services or it can

reflect a weakening economic base and the spreading of costs across fewer

people. Over the last ten years,

population actually shrank in four out of five of these cities – the exception being

Sudbury which saw its population rise 2.3 percent over the last ten years. Yet even in Sudbury, spending rose faster

than population given t per capita expenditure is growing.

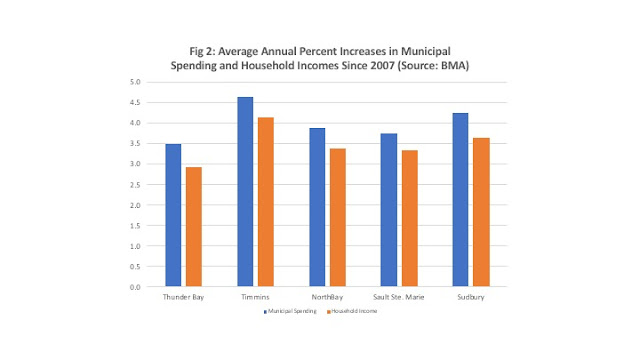

More interesting, is figure

2 which plots the average annual growth rates of the net municipal levy per

capita (from 2007 to 2017) and average household income (2010 to 2017). In all of these

cities, per capita municipal spending has been rising faster than average

household income. So, it would appear

that in all of these cities, municipal spending has generally risen faster than

both population and income. This suggests that recent years have seen municipal spending outstrip the resource base in these communities as measured by population and income. Indeed, sustainability for sub-national governments has been outlined as a key concern in a recent federal PBO report. Municipal

ratepayers in all five of these cities should be asking how candidates for

their ideas on how they plan to address the fiscal sustainability of their

cities?