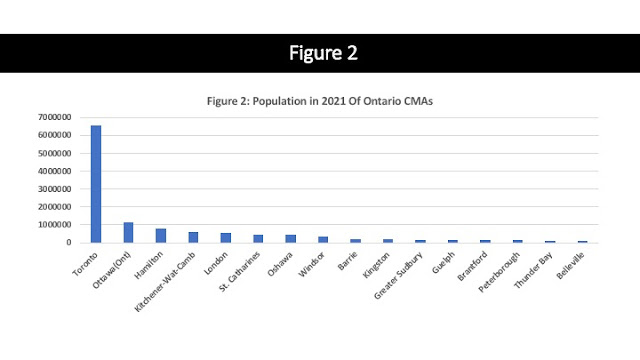

Ontario universities saw the release this week of the preliminary application statistics for the 2023-24 academic year by OUAC, and they are quite intriguing given that they suggest that there may be a shift underway in how students both apply and make their ultimate choices. These applications are for full-time, first-year, fall-entry, undergraduate university study or 101s as they are known, and applications are up 2.9 percent this year though the number of applicants is down slightly by about one-firth of one percent. Figure 1 plots both applications and applicants over the period 2014 to 2023 and though both exhibit a rising trend the number of applicants has been more volatile as a result of the pandemic year.

What is more interesting is Figure 2 which divides the number of applications by the number of applicants in each year and reveals that over time individual applicants have been applying to more universities. From 4.6 applications per applicant in 2014 to 5.8 in 2023. This suggests that students are open to considering more options either because they are shopping around or perhaps to ensure that they get into a program they desire. In any event, this alone suggests that university recruitment out of Ontario high schools may be getting a bit more competitive.

More evidence to this effect is provided in Figures 3 to 5. Figure 3 ranks Ontario’s universities with constituent affiliated campuses included with the main campus (for example, King’s, Brescia and Huron are included with Western) and there is definitely a pecking order in terms of application totals: Large (University of Toronto, York, McMaster, Toronto Metropolitan, Western, Waterloo and Guelph: 59,218 to 40,461), Medium (Queen's, Ottawa U, Wilfrid Laurier, Carleton, Brock, Trent, Ontario Tech, and Windsor: 37,638 to 10,665) and Small (Lakehead, Laurentian, Nipissing, OCAD, Algoma and Universite de l'Ont Francais: 3573 to 22). Yes, 22 for Universite de l'Ontario Francais which because it had only 14 applicants last year it registers the largest percent increase in 101s of all Ontario universities at 57 percent making it such an obvious outlier that it is omitted from Figure 4.

Figure 4 plots the universities ranked by the percent increase in preliminary 101 applications in 2023. Some of the largest increases are for smaller universities. Of the top 10, only two are in the large university category – Guelph and York – while four are in the medium category – Windsor, Ontario Tech, Wilfrid Laurier and Brock - and the other four are all smaller institution – Nipissing, Laurentian, Lakehead and Algoma. Coincidentally, all four of these are in northern Ontario. Figure 5 plots the percent increase in 101s applying in 2023 against the number of applications in 2022 for these institutions and there is a definite correlation between size and growth. Smaller places in terms of previous application numbers on average seem to be seeing higher growth in applications this year.

Now, to keep things in perspective, this does not mean that

University of Toronto or McMaster are going to have trouble filling their first-year

classes this year. The main competition

is still between the bigger places. They have way more applications than they

need to fill their spaces making them still the overwhelming choice for most. The seven largest universities ranked by

applications accounted for about 64 percent of applications. The eight medium sized places accounted for 34

percent and the remaining small universities accounted for just over 2

percent. The small furry mammals are hardly

a threat to the larger denizens of Ontario’s university system. Still, the fact that their application

numbers are up suggests that some students may be becoming more open to venturing

outside their home communities which are invariably close to the GTA. As well, students in these communities with smaller universities may be deciding not to go to school in higher cost centers. The cost of living in the GTA for students

away from home is undoubtedly a factor in these inflationary times and so we

may be seeing the smaller more out of the way places improving their enrollment at

least at the margin. This should hopefully spill over into budgetary positions given that Ontario universities have faced freezes in both their tuition and government grant revenues.