As expected, Monday evening’s City Council Meeting was a

long one wrapping up at 3am and as predicted the Turf facility is going forward

if by a slim margin of

7-6 in favour. For the record to assist you in decision

making next election, those in favour of spending more money despite the

caveats: Mayor Bill Mauro and councilors Albert Aiello, Shelby Ch'ng, Andrew

Foulds, Cody Fraser, Kristen Oliver and Aldo Ruberto. Those in favour of delaying the project in

light of the current situation: Mark Bentz, Trevor Giertuga, Brian Hamilton,

Rebecca Johnson, Brian McKinnon and Peng You.

In the end, Mayor Mauro got what he wanted and one wonders why he risked

so much political capital to drive something that a large

majority of the public seem to oppose.

The evening also discussed the budget and originally there

was a proposal to raise the 2021 tax levy by 3.45 percent in order to deal with

the $8.4 million in COVID-19 expenses – though left unexplained is why with $9

million in provincial and federal assistance coming, are those costs for 2020

not largely taken care of. In the end,

apparently the increase is now proposed at only 2 percent but that will likely

change given Thunder Bay’s deteriorating tax base and the “need” for more

money. And, there was plenty of evidence

in the documentation for Monday night’s meeting on the eroding tax base.

I suppose there was little time at Monday night’s meeting to

discuss other items of business such as Corporate Report No. R 18/2020 included

in the Committee of the Whole Agenda and buried on pages 236 to 239 (with a

lengthy Appendix afterwards). This report

was on Property Tax Accounts with 2018 Arrears.

Of course, the table of numbers spanning properties that stopped paying

their taxes over the 2008 to 2018 period was probably too much to process for

the bleary eyed councilors. Sometimes

one wonders if City Council is some type of cult designed to ram through

decisions by handing councilors 300 page documents and then depriving them of

sleep with long meetings. Of course, the more alert ones in favor of

the turf facility may have been alarmed at the prospect of discussing the

growing number of tax arrears properties at the same time new spending was

being proposed and heaved a sigh of relief it did get too much attention. Nevertheless, I suspect the numbers

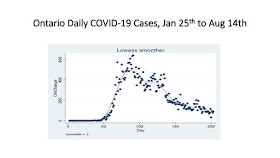

themselves would have little impact - pictures are much better and as usual I

had to provide my own.

Figures 1 to 3 takes the data in the report and plots the

number of properties (both total and residential) in tax arrears, the total

value of tax arrears by year in dollars, and finally the value of those arrears

as a percentage of the total tax levy that year. The plots are disturbing as despite the

occasional up and down, they show a clear upward trend over time. Whereas the average annual number of

properties in arrears from 2008 to 2010 was close to 100, for the 2016 to 2018

period, it averaged close to 300. In essence,

the number of properties in arrears has tripled over the last decade. It is not just business properties, it is

also residential. The value of the tax

arrears in 2018 was $2.5 million – a not inconsequential sum given that the

original proposed tax increase of 3.45 percent would have likely added nearly

$7 million to the tax levy. Indeed, as a

percentage of the tax levy, the trend is also upwards and reflects foregone

revenue – which if looked at cumulatively since 2008 represents the evaporation

of nearly 10 percent of the tax levy.

If property owners in Thunder Bay are stopping to pay taxes

on their properties and giving up on them, there is a serious issue. The solution is not stricter enforcement and

chasing people down by hiring a Sheriff of Nottingham type with a half dozen tax

facilitators and support people to extract the cash. There are probably many reasons why people

are unable to meet their tax obligations and give up on the property they are

holding.

For some, it is being on a fixed income or job loss or

health issues. Some are seniors with dementia

whose families have lost track of the properties. For others, it is a simple calculation: - given

diminished circumstances, the value of what they own is not worth keeping given

the tax burden that has been imposed.

This is apparent from some of the properties listed which are

undeveloped lots and properties being taxed at high rates but often in

locations where there is no prospect of them ever being developed let alone a

market buyer found due to plans, zoning rules and regulations that only Thunder

Bay insiders can navigate.

What kind of city lets this happen? How can so many councilors talk incessantly

about how they care about social justice and equity and helping the socially

deprived and at the same time not realize the long-term effect of their decisions,

policies and actions in raising the economic burden on workers and families in Thunder

Bay? It is not just a provincial or

federal responsibility. Its theirs too.