Labor markets are at the forefront in terms of current policy issues given the shortages that are plaguing so many sectors in Canada's economy. During the pandemic year, employment in Canada took a major hit but had largely recovered by the end of 2021. When we look at employment and jobs in Canada using data from Statistics Canada, our usual approach to where the jobs are is something akin to what we see in Figure 1 below. Canada has 35 major Census Metropolitan Areas (CMAs) each of which is a regional labor market on its own with employment opportunities that need to be filled and employment that is created. Canada's largest nodes of employment are Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver with average monthly employment in 2021 at 3.4, 2.4 and 1.5 million jobs respectively. The numbers fall quite dramatically after that and by 11th place London you below 300,000 jobs. Twelve cities have fewer than 100,000 people employed ranging from Guelph at an average of 91,000 to Belleville which is just below 50,000. Incidentally, Thunder Bay has the second smallest total number of jobs of these 35 Canadian CMAs.

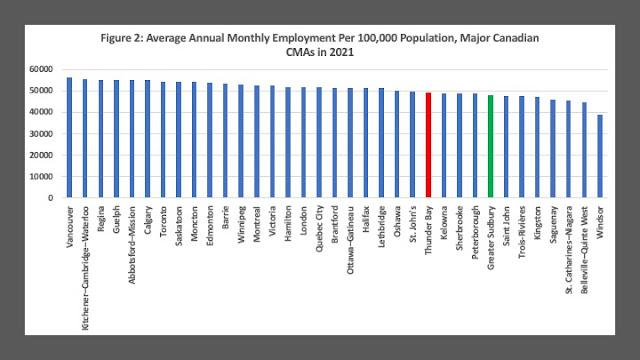

Of course, larger population centers generally are going to have more total employment. Another way to look at employment is in terms of employment intensity or density. In per capita terms, do some cities simply have more employment depth or density adjusted for population meaning ultimately more jobs and opportunity? This is done in Figure 2 where the same cities are now ranked in terms of employment per 100,000 population. The falloff from the top to bottom performers is no longer as dramatic when the comparison is done this way. Vancouver is now the most employment dense CMA with 56,507 people employment per 100,000 population while Windsor is the least employment dense at 39,122. Thunder Bay moves up significantly from the previous ranking now placing 24th out of 35. Meanwhile, Toronto is not as employment dense as Regina or Guelph but tops Saskatoon and Moncton.

A historical point: Thunder Bay's CMA population has not changed much in 40 years but its total employment prior to the forest sector crisis of the early 2000s used to fluctuate between 65,000 and 70,000 jobs whereas now it fluctuates around 60,000. That means that several decades ago, Thunder Bay was more employment dense than the present. Naturally, a historical examination of employment density is in order for many Canadian CMAs but one suspects it would provide answers that many would rather not hear.

Still, if you are looking for employment nationally, it is not just the total size of the labour market in terms of jobs that you should be looking at but also the density of employment. On the one hand, places with low employment density may be facing more of a labour shortage and therefore be a source of opportunity. More likely, places with higher employment to population ratios are simply more dynamic economically and have more opportunities to offer. Places with low employment to population ratios may simply be more economically depressed that those with higher ones.